Tettsu Gikai and Parental Mind

Rick Fumyo Mishaga

“In the same way that a parent cares for an only child, keep the Three Treasures in your mind.”

[Dogen Zenji in Tenzo Kyokun]

It was spring of 1237. Dogen, the founder of a fledging monastic community just south of Kyoto, had finally finished his Tenzo Kyokun, “Instructions for the Chief Cook.” This was one of a series of operational essays he had been developing for the monks in training. He was setting forth monastic regulations in the tradition of the Chinese monasteries where he trained over 10 years earlier. But most importantly for future generations, Dogen was also describing how enlightenment is actualized within normal daily activity. In the Tenzo Kyokun, Dogen presents three attributes or qualities of mind that define a mature Buddhist practitioner such as a Chief Cook: kishin (joyful mind), daishin (magnanimous mind), and roshin (parental mind). The quality of roshin, parental mind, is the selfless concern that exemplifies a parent’s devotion to her/his child. Dogen says this attitude is how all tasks should be approached and how all things should be used “ . . . when you handle water, rice or anything else, you must have the affectionate and caring concern of a parent raising a child.”

Dogen was characteristically precise in his selection of parental mind as the expression of loving concern, for the qualities of parental mind uniquely portray enlightened activity. For example, parental mind expresses the attentiveness that naturally arises from the oneness beyond the physical body. The child is the immediate extension of the parent’s biological reality. Parent and child share the same genetic material, they hold the same family history and hopes, and for better or worse, they stand in the same karmic stream.

As a metaphor for enlightened activity, parental mind expresses loving concern without attachment. Every action springing from a parent’s concern ultimately has but one purpose — to prepare the child to leave home and to dissolve the dependent parent-child relationship. The successful parent, regardless of his circumstances, does not hinder this separation. He nurtures his child and prepares the child to make his way as a responsible adult, unfettered by emotional, psychological, or financial attachments.

Parental mind, like enlightened activity, responds and adapts, expressing loving concern according to circumstance. The attention of the infant’s parent focuses on the basic needs — food, warmth, and protection. But as the child grows and his experiences widen, the parental mind responds to the expanding needs to teach and to discipline. Ultimately, as the child becomes a young adult, parental mind is expressed passively, the parent becomes the yardstick, against which the young adult will compare new belief systems and will test the bounds of his actions.

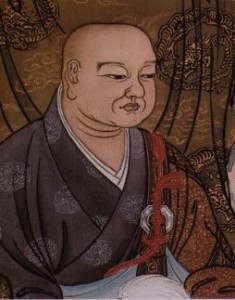

This attribute called parental mind, this quality of action expressing enlightenment, becomes a frequent theme in Dogen’s later writings and lectures. Even during his last days at Eihei-ji, as Dogen was making last minute preparations for a trip to Kyoto for medical treatment at the command of his patron, he found time to admonish a monk for not cultivating parental mind. The monk, Tettsu Gikai, reported that Dogen had chided him once before and now, during Dogen’s final preparations, a second and a third time for not cultivating this quality exemplified by a parent’s selfless concern. In that autumn of 1253, Dogen knew his illness was serious and that he probably would never return to his mountain monastery. It was imperative that he remind this promising monk, a future vessel of the Dharma, to develop the attitude of roshin, which Dogen also referred to as robashin, grandmotherly mind. At that time, Gikai had been a member of Dogen’s monastic community for over 12 years. Dogen’s urging deeply touched Gikai; parental mind became a koan for him because he did not understand why Dogen would repeatedly urge him to develop this quality.

What did Dogen see in Gikai? What was this monk like who evoked the loving admonition of Master Dogen? From his accomplishments, we can surmise that he was a man of action, a man who responded to challenges and got things done. He played a significant, but somewhat understated, role in the formation of the early Soto School and established a firm spiritual and temporal foundation for Zen to flourish in rural Japan.

For his early youth, Tettsu Gikai displayed fortitude, strength of character and directness in vision. As a young monk, he became an accomplished practitioner of Buddhism. He was ordained as a Tendai monk and mastered the Pure Land sutras. He became impatient with Tendai establishment and desired a more direct approach to Buddhism. Therefore, he joined the Daruma sect of Rinzai Zen, practicing under the guidance of Master Ekan. Later in 1241 when Gikai was only 22 years old, he, his teacher Ekan, and other monks of Ekan’s Daruma-shu entered Dogen’s community. Gikai and Ekan wholeheartedly accepted Dogen’s teachings and remained with him. Within ten years after joining Dogen’s community, Ekan was dying. In his final days his friend and disciple, Gikai, nursed and cared for him at Eihei-ji. On his deathbed, Ekan transmitted the Daruma-shu lineage to Gikai and recognized him as his successor, apparently with Dogen’s approval.

Tettsu Gikai won the confidence of both Dogen and Koun Ejo who relied on him to undertake critical tasks for the survival of the community. In 1243 at the end of the summer ango, Dogen moved his community from Fukakusa near Kyoto into the mountains of Echizen. However, the itinerant band of monks had to wait out that first winter in a mountain hermitage because the land at the site that was to become Eihei-ji had yet to be cleared. During this transitional period, Dogen assigned the position of the Chief Cook to Gikai. This was a weighty responsibility, especially during that first winter when the unsettled community was isolated and holed up for the season. Early stories describe how Gikai traversed the windy, snowbound mountain passes on foot each day to find food and supplies for the monks’ two daily meals.

From these beginnings in Echizen to the end of his life there, Dogen depended on Gikai’s assistance in difficult situations. Even during those last days when Dogen was ill and preparing to leave Eihei-ji, he entrusted Gikai with the temporary administration of his monastery until Ejo, who was accompanying him, returned from Kyoto. Dogen chose Gikai, who at that time was not a temple officer, over other disciples to care for Eihei-ji at the same time he admonished him for not practicing parental mind.

When Dogen died in that fall of 1253, his community at Eihei-ji was confronted with a series of obstacles. Dogen’s desire to develop a Chinese-style monastery at Eihei-ji had not been completely realized. Eihei-ji lacked a total complement of monastic buildings. In addition, the monastic codes, etiquette, and rituals had not yet been fully revealed and incorporated into the monastic routine. Most of the members of the community were Japanese born and educated; they lacked the knowledge of traditional Chinese architectural design elements and of proper Chan monastic procedures. Koun Ejo, Dogen’s successor and second abbot of Eihei-ji, asked Gikai to undertake the perilous journey to China to visit Jingde, the monastery where Dogen trained under Rujing, as well as other Zen monasteries and to acquire the direct knowledge and information for the completion of Eihei-ji. Gikai accepted the challenge and returned to Eihei-ji after a few years in China with design drawings of monastery buildings, information on the proper use of these structures, and copies of monastic codes and ritual practices. Thus, he was directly responsible for the final implementation of the Dogen’s vision for a Chan-style monastery at Eihei-ji.

Koun Ejo transmitted Tettsu Gikai in Dogen’s lineage in 1255 before he went to China. He later succeeded the ailing Ejo as the third Abbott of Eihei-ji in 1267 at the request of the temple’s patrons. Ejo and Gikai discussed Dogen’s chiding of Gikai for lack of parental mind. Gikai finally came to realize the great difference between “enlightenment encompasses all activity” (i.e., “everything is Zen”) and “enlightenment is actualized only within activity.” There can be no enlightenment without wholehearted participation in everyday activities. Gikai understood that it is not what is accomplished in the name of enlightenment or Zen but that wholehearted participation is expressed in the selfless striving of parental mind and, in turn, is the actualization of enlightenment.

Gikai served as Abbott of Eihei-ji for only about five years until 1271. He then built a hermitage nearby and cared for his aging mother there. Although he retired from the administrative duties of the monastery, he returned to nurse his dying friend and teacher Ejo in 1280. Also, it was Gikai who performed the annual memorial services for Ejo at Eihei-ji for the seven years after his death.

In 1293, Tettsu Gikai left the mountains near Eihei-ji with a group of disciples and founded a new Zen monastery, Daijo-ji, at an existing Shingon temple in Kaga. He remained there actively participating in monastic life until his death in 1309. There have been many speculations about why Gikai left Eihei-ji and much has been made of the so-called Sandai Soron, the third generation schism. Fifteenth century monks that represented the strong factional sectarian interests of the time were first to advance this idea many years later. They described Gikai’s leaving as part of a major schism between factions representing Gikai and the other successors of Dogen and Ejo. Modern interpretations find no reliable evidence for a schism and suggest that the several early Soto communities did communicate and assist each other in times of need. Also, Gikai’s preeminent disciple, Keizan Jokin, studied with Gien, fourth Abbott of Eihei-ji, and with Jakuen, Dogen’s disciple and the Abbott of Hokyo-ji; it is unlikely that this would have occurred without Gikai’s cooperation and approval. Perhaps the reason for Gikai’s leaving Eihei-ji is more basic and reflects personality and selfless concern. After having faithfully served his three teachers, Ekan, Dogen, and Ejo, having honored their memories, and having met his filial duties to his mother, Tettsu Gikai at the age of only 74 was ready for a new challenge.

Keizan assumed Abbotship of Daijo-ji in 1298. Gikai while semi-retired still assisted with the spiritual training of the newly ordained monks. He was particularly impressed with the spiritual maturity and talents of one young monk, Meiho Sotetsu, whom he suggested to Keizan as his successor at Daijo-ji.

In 1300 Keizan Jokin presented a series of Dharma talks at Daijo-ji on the ancestors that would later be compiled as the Denkoroku. His final talk presented the life of Koun Ejo. He did not include Tettsu Gikai as the final ancestor because Gikai was still alive, as the monk trainees knew so well, and to do so would have breached etiquette. In the end, Tettsu Gikai learned to embody the quality that Dogen called roshin, parental mind. And as the spiritual parent of our lineage, Tettsu Gikai provided a place for our spiritual wellbeing. His temple, Daijo-ji, and his style of practice continued in our lineage through Keizan and Keizan’s senior disciple, Meiho Sotetsu. It continued on through the generations of Daijo-ji abbots, century after century, surviving the dangerous and devastating rise of the Tokugawa. Even the great eighteenth century reformer, Manzan Dohaku, for whom our lineage is often named, was Abbott of Daijo-ji in the tradition of Tettsu Gikai.

* For the sake of readability, footnotes have been omitted. However, the primary source for the factual contents of this article is William M. Bodiford, Soto Zen in Medieval Japan, Kuroda Institute: Studies in East Asian Buddhism, No. 8, 1993, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 343 pp.